Selecting a company’s next CEO is one of the most significant decisions in an organization’s life. In every company, it is critical to find the right fit; in a family-owned business, the fit factor is even more consequential. The success and sustainability of the family’s main asset and source of income, and a significant piece of their identity, rests largely in the hands of the individual selected to be CEO of their family-owned business.To an untrained observer, choosing the next CEO in a family company may appear apparent and straightforward: the first option is to choose a talented son or daughter of the current CEO—one interested in the work of the business. The next option is to choose a talented relative (a non-lineal descendent), or someone working in the company or from the outside. But it is neither this simplistic nor predetermined as a choice of options, and no family company can afford an error in today’s competitive and fast-changing business environment. An under-performing CEO, or one that is not in sync with the owners’ vision and values, can set a company and a family back, and some companies may never recover or regain their balance, focus and drive.There is much at stake when transitioning executive leadership. Every family business today must pay close and special attention to the selection of its next CEO, and to the succession process. This begins with the recognition that succession is a dynamic process, rather than a pre-determined decision. Too often, business leaders view the CEO transition as little more than the hand-off of a baton. In reality, the continuity of the family business is a true team effort, with a game plan that is drawn up and implemented over time. It involves both generations of owners and business leaders working together to maintain momentum in the company, and continuing to adapt their succession game plan as needed–even close to the finish line.

Selecting a company’s next CEO is one of the most significant decisions in an organization’s life. In every company, it is critical to find the right fit; in a family-owned business, the fit factor is even more consequential. The success and sustainability of the family’s main asset and source of income, and a significant piece of their identity, rests largely in the hands of the individual selected to be CEO of their family-owned business.To an untrained observer, choosing the next CEO in a family company may appear apparent and straightforward: the first option is to choose a talented son or daughter of the current CEO—one interested in the work of the business. The next option is to choose a talented relative (a non-lineal descendent), or someone working in the company or from the outside. But it is neither this simplistic nor predetermined as a choice of options, and no family company can afford an error in today’s competitive and fast-changing business environment. An under-performing CEO, or one that is not in sync with the owners’ vision and values, can set a company and a family back, and some companies may never recover or regain their balance, focus and drive.There is much at stake when transitioning executive leadership. Every family business today must pay close and special attention to the selection of its next CEO, and to the succession process. This begins with the recognition that succession is a dynamic process, rather than a pre-determined decision. Too often, business leaders view the CEO transition as little more than the hand-off of a baton. In reality, the continuity of the family business is a true team effort, with a game plan that is drawn up and implemented over time. It involves both generations of owners and business leaders working together to maintain momentum in the company, and continuing to adapt their succession game plan as needed–even close to the finish line.

During over three decades of advising and studying CEO transitions in family businesses, we have designed, executed, and witnessed a variety of succession plans and transitions, including some detours. Every family business system’s dynamics, goals and timetable are unique. Still, a process that is well framed and executed with discipline–and is unhurried, uninterrupted, principled, fair, and transparent–is the surest way to transition to the right CEO. It is worth the owners’ investment of time and thoughtful planning to ensure that the appropriate individual is chosen to take the company to new heights. It is as important that the ownership group, board of directors, and family are united behind the new leader and his/her mandate.

Context Addressed in This Article

In the best of situations, planning for succession occurs far before the leader’s transition. A generous timeframe of a few years allows for planning, discussion, pivoting, and the development and testing of successor candidates. It also provides a valuable period of time for partnering and mentoring between the outgoing and incoming leader, and addressing matters of harmony and balance in the whole executive leadership team.

But of course, sometimes a leadership transition must take place under unfavorable conditions. It may be triggered suddenly, as in the wake of the early death or incapacitation of the current leader, or unexpectedly, such as upon the ousting of a poor-performing CEO.

This article addresses succession under favorable circumstances, in order to provide a benchmark. The succession process described here is typical for a first generation, founder-stage business transitioning to the second generation, though its lessons are applicable to later generations under similar circumstances. Our assumptions of these circumstances include that the company:

- Is privately-owned and family-controlled.

- Is mid-sized (typically with revenue of less than USD $500 million annually).

- Has moderate levels of complexity in terms of the number of business units, employees, facilities, and geographies.

- Does not anticipate abrupt changes of path in strategic direction, leadership, ownership or governance in the next five years.

In addition, this article’s recommendations assume that the:

- Current CEO is competent and in good health, allowing ample time for the process of searching, selecting, and integrating a new CEO.

- Senior generation has ownership control.

- Family’s relationships are mostly healthy, with normal and manageable levels of rivalry or conflict.

- Family strongly prefers a successor from the family, rather than a non-family CEO.

Succession Planning: The Wrong Way

Typically, in a situation like the one we have set, succession conversations begin with the current CEO asking one of these two questions:

- “Which of my children is qualified to take my place?” or

- “How do I divide up the CEO role so two of my children can co-lead?”

Starting here is a mistake, for several reasons.

First, it assumes that the company should be perpetuated instead of sold, which every departing CEO should question before passing the reigns. On a routine basis, the CEO and board of directors should evaluate the industry’s life cycle, the company’s strengths and opportunities for growth, its market value, and the family’s core competencies and goals in order to evaluate whether the business is still the right fit for the family.

Second, it assumes that the next generation is interested in leading, is capable of leading, or is enthusiastic about sharing the leadership role. Sometimes none of these is the reality, nor has it been discussed in any formal way with next generation members.

Third, it does not engage the next generation in the conversation or the future visioning process for the business leadership and ownership, which can lead to frustrations, suspicions, and strained relationships.

Finally, both these questions tend to imply that the next CEO should have similar views and a similar leadership style, or even be a clone of, the current CEO. These leaders quickly zero-in on a chosen candidate to replace them, and the company has to adjust to fit the candidate, rather than the reverse. In reality, most CEO successors need to have a different profile than the current leader: the competitive environment is evolving quickly; the company has reached, or is moving toward, a different stage of growth; and its business imperatives are changing.

Instead of starting in this way, the thorough approach described in this article suggests a dynamic set of steps. If you are not in a position to plan for succession with such a strategic approach, delegate it to an independent board member. If you don’t have a board of directors or an advisory board, appoint an external, unbiased, and trusted advisor in the role of championing and monitoring the succession process.

• • •

Succession Planning: A Better Way

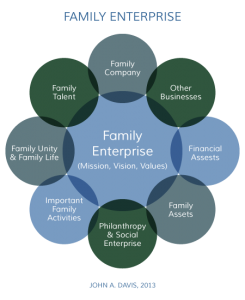

First, the big picture concept is that the family ought to clarify what they are trying to pass to, or sustain through, the next generation. This typically includes the core operating business, but often there is more—such as other operating businesses, perhaps some real estate investments, art collections, philanthropic activities, or other pursuits that carry the family’s name and reputation. The entirety of a family’s financial interests and meaningful activities is called the family enterprise.

When considered as a whole, it is easy to see that it takes a team of people in different leadership positions to make the family successful for another generation or more. The CEO of the core business is a critical position, since the business often represents the most important source of income and networking relationships for the family; but that leadership position isn’t the only one in the system. If the family wishes to renew entrepreneurship in new areas, or to build social enterprises or a philanthropic foundation, additional kinds of leaders could be needed. If the real estate portfolio is poised to grow, a different need for leadership might emerge. New initiatives and ventures offer new opportunities and call for different skills.

When families look together at the total family enterprise, and envision where it is today and where the family wants it to be in the future, members of the next generation often respond to the visioning process with relief: they are able to play an active part in thinking about and designing the future of the family enterprise. They see an array of options where they can contribute in active roles, even if this means that some of them will not enter or lead the core business.

When this overall picture becomes more limpid, the future role of CEO of the core business also becomes clearer for many family members and owners. Then the senior generation leader can enter a strategic process for anticipating the future needs of the company and the skill sets required from the next CEO in ways that better respond to future imperatives.

When to Begin the CEO Succession Process, And How Long to Take

The succession process for the business begins earlier than one might think. On the family side, the next generation’s interest in joining the business, or not, is shaped when they are young and hear their parents’ conversations or feel the impact of the company’s life on their family life. Is the family business a source of tension or joy? Is the business an expression of the family’s creative drive and sense of purpose and identity, or is it an obligatory activity? Does the business enhance family relationships, or does it create divisions?

Therefore, members of the senior generation should take care in how they represent the business to young members of the family, and depict a world where there is room for senior and junior generations to work together. At the same time, it is important to instill a sense of professionalism required for the company’s success in the minds of the next generation. Children should know that the company needs to have the best leader possible to maintain its healthy growth. Start early by engaging the younger generation around both the challenges and the positive benefits of the family business, including the business’ constant need for excellence in people, products, client relationships and so on. This will go a long way toward clarifying some of the fundamentals of the transition process many years down the line.

As for the active succession process for CEO renewal, it should start at least three to five years before the current CEO steps down and no longer serves full-time in the CEO role. Exactly how much time is needed depends on many factors, such as:

- How prepared the next generation is to eventually move into leadership roles

- Whether non-family member candidates will need to be considered because of age or skills gap in next-generation family members

- How ready the current generation is to depart the CEO position

- How complex the organization is

In less complex contexts, a few years may be sufficient; in larger more complex systems, a minimum of five to ten years is often needed. But the important principle that applies to all family businesses of any size or generation, when aiming to keep ownership and leadership within the family, is the following: The most effective succession transition occurs not when the senior generation is ready to leave, but when the next generation is ready to lead.

Importance of the Board of Directors

In most situations of leadership succession in the business, the active role of a Board of Directors (or Advisory Board) will be critical to success. This is true in both situations where (i) a family member is selected as CEO, and (ii) a non-family CEO is selected after an era of family member CEO(s). In the first case, it is delicate for the family member CEO to report to one or more family owners; not only does this make accountability difficult, but it also makes substituting the CEO a sensitive family matter. In the latter case, adapting to a non-family CEO (especially if selected from outside the organization, rather than nurtured from within the organization), involves risks of misalignment in: goals, understanding of the family’s critical needs, and leadership roles to be played by the family owners, the board and the CEO.

We believe that a well-structured board (which can be fiduciary or advisory in the beginning) can greatly enhance the probability of success in a CEO leadership transition. Having the board involved in defining the desired profile and in the subsequent stages of selecting the CEO candidate will make the process clearer and more objective. In addition, once a CEO candidate is selected, the board will help the onboarding and add credibility to the performance evaluation of the CEO, helping him/her define ambitious goals and objectives and provide support and feedback to the CEO in an objective, constructive manner. And finally, if the CEO ultimately is not performing well and / or is not aligned in terms of cultural fit or goals, the board will have the responsibility of recommending appropriate changes. A significant benefit to this process is that it also forces the family owners to confirm how they, and the board of directors, will partner with the CEO, and what will be the boundaries of everyone’s roles and responsibilities.

Succession is a Dynamic Process

When executed well, succession is a dynamic process, not a pre-determined decision. In the best of cases, if the successor is a family member, there is partnering between the senior and next generations for several years, sometimes for a decade or more. The departing CEO often transitions to the Chair of the Board role as the next generation takes the helm as CEO. In these two positions, the two generations can often partner for many years.

In rare situations, the senior generation is of the mindset that the next generation must lead without the oversight of the senior generation, which lends itself to a clean and abrupt transfer of leadership at a given moment in time. But this is more and more uncommon, particularly at the founder or controlling owner stage. Except under extraordinary circumstances, we advise against it. There is profound benefit potential of the two generations leveraging each other’s skill sets and views of the world to make better strategic decisions for the company, as long as each individual’s roles and decision-making allocation are clear.

STAGE 1: PREPARATION AND PLANNING

The succession process for executive leadership is focused on the long-term needs of the business. In other words, succession transitions are made for where the business is going.

Develop the Family’s Vision for the Business

Begin by developing your vision for the future of your business, even depicting a few very different scenarios of where the business may go. Understand where your business is now, how important some of the headwinds may be in the future, and also what kinds of new opportunities for healthy growth may open up in your core business and into some adjacent or non-related businesses. Changes to your business, your industry, and the business environment are inevitable; carefully analyze these, and envision a few configurations and paces of change into the future. This allows you to depict different options for future corporate needs, including the talent needed in the future leadership team.

Ask yourself:

- What is the potential for your business to continue to grow and be commercially relevant?

- Where is your industry now, and where is it moving?

- Who or what are the disruptors to your industry and business model?

- How must your business evolve to remain competitive?

- How can you leverage the unique competencies and skills that the business has mastered over time to develop new business opportunities?

- How are your customers’ tastes and behaviors changing?

- How are global mega trends (such as globalization, technology, and demographics) affecting your industry, your region and your company?

- Are you ahead of these changes, or lagging behind them?

- Is there enough room to grow in your current business, or do you need to expand into different business lines, or even sell your current business?

- What are the owners’ financial needs from the business? Can the revenue and profits generated by the business meet those expectations?

- What does your company need in order to thrive and to achieve the family’s long-term vision for the company’s growth and development?

- What does your company need in order to achieve the family’s long-term vision and mission?

Develop the Profile for the next CEO

Given your analysis of these important areas, hone in on the pertinent questions related to CEO succession:

- Given where our industry and business are going, what are the leadership needs of the company into the near future (2-4 years)?

- And from a longer-term perspective (5 years +)?

- What do we expect of our next CEO?

- What are the objectives for the next CEO (as an individual and for the company)?

- What kind of mandate will we give to the next CEO? Squeeze costs? Grow through some acquisitions? Divest some activities?

As you ask yourself these questions, begin to create a profile for the leader based on the company’s needs—irrespective of any individual candidates.

Develop the Vision for the Family’s Role in the Business

Then, develop your vision for the potential continued role of the family in the future business.

This is a wonderful time for family members to talk about their future together. The family owns a common asset – the business – or they will own it together once some ownership is acquired by, or shared with, next generation members. And even if some family members are not owners, they might receive income from working in the company as an employee, or leverage the networks and reputation developed by the company to help their professional career outside of the company. How does the family want to care for that asset collectively? How do they want to nurture it? What do they want from it? Or does the family feel that selling it might be an option that needs further investigation?

Initiate important conversations about the family’s highest and best use in the business.

- In what roles will each family member add the most value?

- Where is the family collectively capable, and not capable?

- Where is the family essential, and where can it delegate to non-family?

- Where will non-family talent be critically needed?

Consider Potential Candidates

Now, looking at your newly developed CEO profile, and your understanding of the family’s capabilities and goals, consider whether any members of your family’s next generation have, or are building, sufficient skills and interest to match that profile in the near-term or longer-term. If so, begin a communication process with the board of directors, the board of advisors, or some close advisors, as well as the family and the candidate(s) in due time. If there are one or a few candidates from within the family, the process of clarifying expectations among them is crucial.

If no candidate emerges, the best decision for the perpetuation of the business may be to delegate executive leadership to a non-family member, at least for a certain number of years, and for the family to lead strategically from the board of directors and their ownership roles, partnering closely with the new CEO. In this case, a different process is used to source non-family CEO candidates, either from within the company or externally. This process is not addressed in this article.

Plan the Senior Generation’s Next Act

The outgoing CEO must take the time to plan scenarios for his or her life path. What is your highest and best use in the organization after you depart the CEO role? If you will move to the Chair of the Board role, what is your new mandate? What does the next generation need from you? What are your personal goals outside of the business? How will you define your next roles and occupations to lead a satisfying life while being useful to the family? What kinds of resources, including income, will you need to lead a comfortable life?

Define a Roadmap for the Succession Process

As the final step in this planning stage, define the roadmap for the succession process over the next three to ten years, depending on your context. Designing this roadmap requires active leadership by the senior generation.

Determine who will lead the process and bring some neutrality to it:

- Who will help articulate the different feasible options?

- Who will facilitate discussions?

- Who will monitor progress, anticipate some of the knots, and suggest ways to untie them?

- What level of engagement is needed from the current CEO, the board of directors or advisors, the owners, key managers, the family, and external trusted advisors?

- Who will provide constructive feedback on a regular basis to all those involved?

Decide what the major milestones will be, and set a timetable. You will likely revise it from time to time, but having a timeline will help to clarify the phases and steps for the current leader and the CEO candidate(s).

Set criteria for the successor’s readiness for the job of CEO—it will be your barometer throughout the succession process. With this, you will be ready to assess a successor’s development needs, and begin grooming him or her to ensure success.

Determine how and when you will communicate to various stakeholders so they are informed, included, or consulted.

STAGE 2: IMPLEMENTATION, ADAPTATION, AND TESTING

This stage is devoted to getting the next generation successor ready for the CEO position. It is a cycle of developing, testing, and assessing the candidate. This process often takes between two and four years (though it can take longer), depending on how experienced and ready the successor is for the role, and whether he or she is already working in the family business.

If there is more than one successor candidate in the next generation, make sure the process of development and assessment of candidates is crystal clear. Surround them with proper mentors and coaches to assist in their positive experience of the process. Make sure that there is a ‘plan B’ for those who will not make the cut: either provide them with career orientation, some other leadership roles in the family enterprise suited to them, or other forms of assistance in finding their own path to a successful life.

Conduct Assessments of the Candidate

Begin by conducting a thorough assessment of the successor candidate:

- Skill sets (with the help of skilled facilitators and assessment tools that provide insightful analysis)

- Leadership and management capabilities

- Experience (including an understanding of where and how in their life up to now they have developed tangible competencies and valuable experiences)

- Knowledge of the industry and of the company

- Understanding of the owners’ vision for the company

- Understanding of the owners’ values and what they deeply cherish (sometimes our assumptions may be wrong, since we have seen the owner-founder at home rather than in the work environment)

- Ability to partner with the current CEO, management team, board of directors or advisors, owners and family

- His or her personal view of the long-term vision and strategy for the company

- Character, personality, and personal values

- Ability to serve as the right ambassador for the family within the company, and as a representative of the company and family externally

- Any other dimensions important to the family and company.

It is not uncommon to conduct a psychological evaluation of the successor candidate at this time to provide greater insight and assurance that we will later understand their behavior under stress and fatigue, for example.

Identify the gaps between what knowledge, abilities and experience the successor candidate has and what he or she needs to succeed. To benchmark, use the leadership profile and list of readiness criteria which you developed in Stage 1.

Design a Development Program

Design a development program for the candidate to fill the skill and experience gaps. If the successor is not yet working in the family business, invite him or her in to learn the business, interact with the management team, assimilate into the culture, spend time with the owner(s), and be overseen by the board or external advisors.

Every succession plan looks different in this area, but here are examples of some components and stretch assignments for a development program:

- Understanding of the different ‘hats’ that a working owner wears – owner, leader, board member, family member – and which hat to wear upon arrival at the company and in various situations. Next generation members who come in with even the tiniest entitlement behavior will be quickly shut down by others, not necessarily in a visible way, but it will be felt in their day to day interactions with employees. A CEO successor cannot afford to lose credibility in this manner.

- Rotated training through different business units of the company, different geographic regions, and different roles in order to deeply understand the operations, technology, customers, needs, and culture of the company (and gain more feedback on the candidate).

- Responsibility or some form of active role for a struggling project or declining area of the business with a goal to turnaround, improve, modify, sell, or close it.

- Responsibility for specific projects, small and large, with tangible outcomes for assessing leadership and measuring performance.

- Responsibility to start something new, such as open a new office, enter a new market, or launch a new product.

- Responsibility to lead a team, provide feedback, and have difficult conversations.

- Formal classroom education to learn needed skills (leadership, organizational change, corporate finance, negotiation, and so on).

- Mentoring from the CFO, or external advisors if necessary, to develop a deep understanding of how to read and interpret the company’s financial statements, legal structure, and tax optimization strategy.

- Executive coaching to build or improve important soft skills.

- In due time, ‘public relations’ opportunities to speak to the management team, the employees, customers, suppliers, lenders, and the media.

- Regular presentations to the board of directors or advisors so they can evaluate the candidate’s growth.

- Regular interaction with the family and owner(s) so the larger family begins to shift their recognition of the individual from a next generation family member to our future leader.

Provide the Candidate with Regular Feedback

For each assignment, provide goals and constructive, transparent feedback to the candidate successor so he or she understands that this is a performance monitoring stage, and that he or she will be evaluated. Be clear about the evaluation criteria and how success will be defined, and have check points along the way. Suggest sources of assistance and coaching when needed.

Feedback should not be given by the current CEO, but by objective outsiders, such as the board, a non-family manager, a facilitator, a coach, or a combination of these. These are regular, respectful conversations, but the overall message should be that the family will prioritize the company’s healthy growth in this process, and the successor will be promoted based on merit.

A Potential Interim Role

As the candidate develops, he or she may assume the COO role, working closely with the CEO for some time, as a final step before transitioning to the CEO position. In many organizations, the COO directly manages internal operations; while the CEO leads strategy development, achievement of strategic objectives, and external and institutional relationships, as well as acts as the primary liaison to the board, and often to the other owners, and the family. Regardless of how the roles are defined, having a mutually supportive working relationship between the CEO and COO is as essential as having clear reporting relationships in the company in order for this dual leadership structure to function well.

Appoint the Incoming CEO

The board or trusted advisors eventually deliberate with the current CEO, and if they deem the successor ready, recommend to formally appoint the successor as the next CEO. If there is no board, then the owners appoint. However, this is a prudent time for the senior generation to consider assembling a competent board, which offers many benefits.

The CEO’s mandate from the board or owners, performance measurement system, compensation and incentive package, and all other areas requiring clarity should be addressed at this time. Once finalized, the owners, the family and employees are notified first; then a public announcement is made.

Support for the Departing CEO

The outgoing CEO will need to spend some time mourning the past, and accepting a new identity as former CEO. This is a healthy and necessary part of the process, and not something to bypass. If you have a board, and if you plan to have a role on it, then spend time well before the new CEO comes in, to shape the Chair role for yourself or other key roles. Clarify your mandate with the help of board members and advisors, and accept your new identity. Remember that you still have an important role as a mentor to the incoming CEO, as a senior owner, an important family member, and as a “family unifier,” as you assimilate into this next phase of your life.

STAGE 3: TRANSITION AND STEADY STATE

Once the new CEO is in place, and the outgoing CEO becomes Chair of the Board or involved in other activities, there is still time for solid partnering between the two. We recommend a period of at least one year, where the former CEO and new CEO work closely together – on specific tasks, business issues, or initiatives that have been defined together. This ensures that all parties are integrated, working on alignment, and partnering. It will strengthen the relationship with the family, key customers, suppliers, and stakeholders. It is stabilizing for stakeholders to know that the transition is smooth and that there is substantial overlap.

It is important to note that the role of the Chair of the Board must be clearly defined. This is not a disguised title for hanging on to the CEO position. That would undermine the new CEO, which leads to collateral damage that the organization ought not spend its resources managing.

Of course, in some instances, the former CEO may choose to retire and leave the company completely, without serving on the board. If there has been thoughtful partnering throughout, this can be a seamless transition. In this case, having a strong board is even more critical in overseeing and partnering with the new CEO.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Achieving a smooth and successful CEO transition is an arduous process. It requires energy, discipline and focus. Many obstacles will arise along the way, and many emotions will present themselves to sort through. Families that remain respectful and united throughout the process will be stronger for it. Therefore, communication and appreciation among the family is key.

Below are ten typical pitfalls to avoid:

- Elongating the planning process without action: taking too long to plan; doing too much analysis; not being decisive enough along the way.

- Being unwilling to change the company or the profile of the leader from that of the current CEO.

- Senior generation resisting letting go, often changing their mind and points of view over things, or not actively leading the succession process and shaping the new role of the next CEO.

- Moving the goal posts: telling the successor what is required to perform, then when those metrics are achieved, introducing a new set of metrics. This is a sure way to demotivate the successor and create confusion in the organization.

- Not providing clear goals or honest feedback to the next generation and successor candidates.

- Allowing politics (in the family or in the company) to contaminate the process.

- Senior generation not publicly affirming the new leader.

- Senior generation joining the board as Chair and continuing to fulfill the duties of the CEO, undermining the new CEO.

- New CEO not including the owners in important discussions and decisions, and not keeping the family informed.

- Neglecting to publicly and overwhelmingly show appreciation to the departing CEO.

The way to avoid most of these pitfalls is with planning, communication, and a principled approach. Don’t wait to begin. Map out the process, make it transparent, and embrace it.

Partnering between the two generations is also vital: it ensures that the planning and implementation process is a team effort with a common goal and shared responsibility for the outcome, and that it is done with respect and empathy. Make sure to celebrate achievements of milestones as you move forward. The succession process takes time. Try not to lose energy and clarity of where you are along the way.

Succession planning will be one of the most important processes your family business will undertake. Give it the time and attention it deserves, and it can result in victories for every aspect of the family enterprise system—a thriving business, effective ownership, and stronger family relationships.

• • •

It is important to note that succession of both leadership and ownership are essential. Leadership succession gets most of the attention of boards of directors, business schools, and the literature—and is the sole focus of this article. But succession involves passing management and at some point ownership to the next generation. In a forthcoming article, we will address ownership succession.

Dr. Pascale Michaud

Courtney Collette is a Partner and Head of Education & Research at Cambridge Family Enterprise Group (CFEG). Since 2011, she has led its education programming, research studies, and publications. She designs curricula for seminars, workshops, and online courses for family enterprise audiences worldwide. She has authored several publications on family enterprise, including articles, Harvard case studies, and the book, Next Generation Success. Ms. Collette spent over a decade as a trusted advisor to business families on governance, succession, next generation readiness, and family unity.

John A. Davis is a globally recognized pioneer and authority on family enterprise, family wealth, and the family office. He is a researcher, educator, author, architect of the field’s most impactful conceptual frameworks, and advisor to leading families around the world. He leads the family enterprise programs at MIT Sloan. To follow his writing and speaking, visit johndavis.com and twitter @ProfJohnDavis.

The Owners’ Mindset in the Age of Disruption

The Owners’ Mindset in the Age of Disruption  Principles of Founder Succession

Principles of Founder Succession  Business Strategy

Business Strategy